To be fearless is to let the creative impulse take you where it will. …

Abby Frucht and I went deep when we chatted about writing, process, and Hold Me Down back in October. The original interview ran on the JMWW blog, and I’m now reprinting it here:

NO HOLDS BARRED: AN INTERVIEW WITH CLEA SIMON BY ABBY FRUCHT

· by jmwwblog · in Interviews. ·

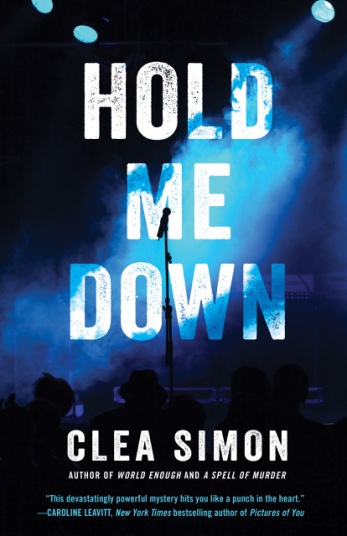

Clea Simon is the author of the upcoming psychological suspense novel, Hold Me Down (Polis Books, October 19, 2021), as well as the recent A Cat on the Case, the third in her “Witch Cats of Cambridge” series. She is also the author of World Enough, a rock ‘n’ roll noir, as well as the Blackie and Care series (most recently “Cross My Path”) chronicling the adventures of the pink-haired Care and the black feral cat who loves her. In addition to these darker books, she is also the author of the Dulcie Schwartz feline mysteries, the Pru Marlowe pet noir mysteries, and the Theda Krakow mysteries, as well as three nonfiction books, including The Feline Mystique: On the Mysterious Connection Between Women and Cats. The recipient of multiple honors, including the Cat Writers Associations Presidents Award, she lives in Somerville, Massachusetts, with her husband, Jon Garelick, and their cat, Musetta.

Abby Frucht: Gal, the rock musician and song writer at the center of Hold Me Down, thinks of her history as being ingrained in the “blonde and battered wood” of her bass. As rock critic, author of countless mysteries, and writer of non-fiction about cats, fathers and daughters, and a loved one’s mental illness, in what object or entity, palpable or impalpable, varnished or worn, does your history reside?

Clea Simon: Probably in the small but beloved collection of books from my childhood that have accompanied me now through six decades of moves, family changes, and more. They take up less than a shelf in my office, but those books—the Robert Graves/Maurice Sendak collaboration The Big Green Book, Frog and Toad, Remy Charlip’s Arm in Arm, Frog and Toad, and a copy of The Wind in the Willows, given to me by a camp counselor when I was stuck in the infirmary for a few days, among others—are my rock. They’re a comfort, sure, but their playfulness and imagination continues to inspire me. In retrospect, these books made themselves invaluable to me because they spoke to me as no adults did. They took me seriously but also acknowledged that reality was not what was always acknowledged. In a Bruno Bettelheim way, sure, but also in the sense that they respected the possibility of the impossible—that scene with the god Pan in Wind in the Willows? That’s awfully heady stuff. This may not sound relevant to my current writing, or to the rock and roll years of my twenties, but it is. Those books keep me in touch with some free, wild part of myself.

AF: When for the first time in years Gal meets up with her band’s former guitarist, the guitarist, now a lawyer, presses her card into Gal’s hand saying, “Please…If you want to talk.” I love that Gal has no clue what Shira is suggesting they might talk about, and I like that the reader has no clue, either. When did you yourself know what Shira hoped they’d talk about? Did you already know, when writing this scene, the revelations that would come of their conversation-to-be, or did Shira’s invitation propel you to keep writing and find out?

CS: I knew early on what Gal was not acknowledging, but the way these conversations played out—largely with Shira, but obliquely with Lina and others—was a surprise to me. As I crafted the manuscript, I was aware of wanting to obscure some things and keep others vague. That Gal’s defenses would cause her to misinterpret and misdirect her rage. But I was both surprised by and very much loved how Gal ends up revealing so much of herself through her music, even as she remains blind to her own expressions for so long.

AF: “The crowd feeds the performer,” Gal notes of her drug-fueled nights on the road. “There’s a charge from being onstage, something mutual.” Where does “that rush” come from for you as a writer. And do you ever dare wish you might feel, again, as if you “didn’t have flesh. Have skin,”?

Clea Simon: Oh my god, yes—but I do! I do feel that way when the writing is going well. For me, now, it is that feeling when all the gears hit that I don’t exist as a writer—that I am channeling something fully formed that is out there and waiting. I love that I don’t always know what that something will be, or what it is saying about me. What writer doesn’t? When I was nearly done with the first draft of my 2017 mystery, World Enough, which is also set in the music world, I realized there was a horrible plot twist set up that I hadn’t been aware of. Of course, when I re-read, I saw that the seeds for it had been planted all along, and so of course I let it play out. It gave the book a certain poignant ambiguity, right at the end, and I like to think that it makes the book, which was named a “must read” in the Massachusetts Book Awards. Much of Hold Me Down was like that – just trying to surf what emerged.

I think this feeling of being without flesh, without a controlling consciousness, is vital. If you have complete control of your work at all times, you’re not allowing that other element in—the magic or the subconscious. Whatever that truly creative part is. For Gal, and, certainly, at times, for me, I have wanted to be swept up in that feeling to avoid a reality—I have let things out of me in an almost automatic, unthinking way that I did not want to acknowledge consciously. But it’s more than that. It’s the reason I write and also the best part of the writing.

AF: Gal is a rape survivor. Acts of vengeance, murder itself, and the question of making amends are at the core of her urgent and important story. Do you feel that a rapist’s even genuine repentance might be meaningful to his victims?

CS: I don’t care about a predator’s repentance, except in that it might mean that predator is less likely to attack in the future. I don’t think it’s relevant to anyone but the perpetrator. A few years ago, I was contacted by the roommate of the man who raped me in college. He wanted to know if I wanted to talk about the experience. His outreach made me furious. Why would I want to talk to someone who was at some level complicit? Why would I care? Perhaps there is such a thing as genuine repentance, but too often—as in my case and in Hold Me Down—it’s simply self-serving. What I do think is meaningful is the survivor’s rage and pain. Let that be heard.

AF: Gal’s fans called her “fearless.” What does it mean to be fearless in art?

CS: To be fearless is to let the creative impulse take you where it will. Yes, there’s a ton of craft involved in shaping that initial impulse into its best, most complete form. For me, it often seems like that wild first draft is a sketch, a rough that barely suggests the original concept—I think of it as leaving more in my head as opposed to on the page—and the vast bulk of the work is in revision, editing, re-reading, re-writing. That’s the time-consuming and often dreary part. But the fearlessness has to be in the conception, in allowing the piece to become what it wants to be, even if it’s painful, messy, or mean.

Abby Frucht won the Iowa Short Fiction Prize for her first collection of stories in 1987 and has since published eight books of fiction. Maids, which breaks from that tradition, reckons in poetic form with Frucht’s memories of the women who cleaned her parents’ house when she was a girl—a doctor’s daughter—on Long Island. Frucht lives in Wisconsin and has served as mentor and advisor at the MFA program in Creative Writing for more than 25 years. You can find her along with some of her essays at www.abbyfrucht.net. You can find Maids for sale on the Matter Press site.Advertisement